In the realm of traditional cookware maintenance, few rituals are as revered – or as misunderstood – as the Chinese iron wok seasoning process. The technique of rubbing pork fat across a scorching iron surface to create that legendary black patina isn't just culinary folklore; it's a chemical transformation that bridges ancient wisdom with modern kitchen science.

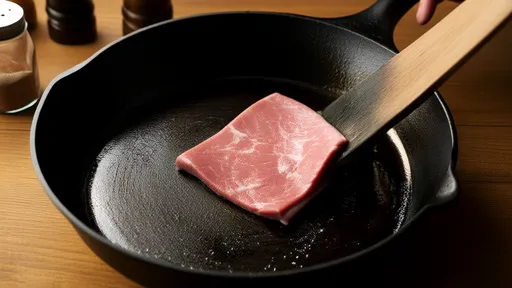

The magic begins with selecting the right cut of pork fat. Professional chefs insist on using fresh, unprocessed pork belly fat with the skin still attached. This particular cut contains just the right balance of collagen and unsaturated fats that polymerize perfectly under high heat. The fat cap should be about two fingers thick – too thin and it won't withstand multiple seasoning rounds; too thick and it won't render properly.

Seasoning a wok isn't simply about creating a non-stick surface. When done correctly, the process forms a carbonized polymer coating that's virtually indestructible. As the pork fat smokes and breaks down during those three crucial applications, it undergoes a molecular change. The fatty acids combine with iron oxide to form iron carboxylate, while the carbon forms an intricate lattice structure that fills the wok's microscopic pores.

Timing and temperature prove critical throughout the seasoning process. The first application should occur when the wok reaches approximately 400°F – hot enough to make water droplets dance, but not so hot that the fat instantly combusts. Each subsequent application requires gradually increasing the temperature, with the final round approaching the fat's smoke point around 500°F. This stepped approach allows for proper layer bonding.

Traditional cooks pay close attention to the changing colors during seasoning. The initial silver-gray iron transforms to golden yellow after the first fat application, then progresses through shades of amber and chestnut before achieving that coveted ebony sheen. This chromatic progression indicates the formation of different iron oxide layers, with the final black magnetite (Fe3O4) providing superior corrosion resistance compared to the red rust (Fe2O3) that forms on poorly maintained woks.

The circular rubbing technique matters more than most beginners realize. Moving the pork fat in concentric circles from the center outward ensures even heat distribution and prevents the common pitfall of edge burning. The pressure applied should be firm enough to squeeze out steady fat rendering, but gentle enough to avoid scratching the developing patina. Many masters recommend using long-handled tongs and rotating the wok handle continuously to maintain consistent contact.

Between applications, the wok requires proper cooling periods. Rushing the process by applying subsequent layers too quickly leads to a weak, flaky coating. The iron needs time to contract slightly after each heating cycle, creating mechanical bonding sites for the next polymer layer. This explains why the traditional three-application method spans several hours rather than minutes.

Modern science has confirmed why this centuries-old technique works so well. Electron microscopy reveals that properly seasoned woks develop a microstructure resembling ceramic glaze, with iron carboxylate crystals interlocking with carbon deposits. This composite material exhibits remarkable thermal stability, maintaining integrity even at temperatures exceeding 600°F where most synthetic non-stick coatings begin to degrade.

The choice between animal fats and vegetable oils for seasoning sparks endless debate among wok enthusiasts. While plant-based oils can create serviceable coatings, pork fat's unique fatty acid profile – particularly its balance of palmitic, oleic, and linoleic acids – produces a more durable matrix. The slight impurities in rendered lard actually benefit the process by providing nucleation sites for more even polymerization.

Maintaining the seasoned coating requires understanding its living nature. Unlike synthetic non-stick surfaces, a wok's patina constantly evolves with use. Gentle cleaning with bamboo brushes preserves the coating while allowing it to slowly thicken over years. Harsh detergents strip away immature polymer layers, while insufficient cleaning leads to rancid fat buildup – hence the wisdom of the three-application method establishing a robust base.

Regional variations in seasoning techniques reveal fascinating adaptations. In humid southern China, cooks often add an extra fat application to create a thicker moisture barrier. Northern methods frequently incorporate a quick vinegar wash before seasoning to ensure perfect metal cleanliness. Sichuanese chefs sometimes rub chili oil as a final layer to impart subtle flavor notes.

The true test of proper seasoning comes during cooking. A well-prepared wok exhibits non-stick properties rivalling modern coatings, yet can achieve the intense heat necessary for authentic wok hei (breath of the wok). Food releases effortlessly while developing that characteristic smoky depth impossible to replicate with other cookware. This duality of non-stick performance and high-heat capability makes the traditional iron wok irreplaceable in professional kitchens.

Beyond functionality, the ritual connects modern cooks to culinary heritage. Each swipe of pork fat continues an unbroken technique dating back to the Han dynasty. The resulting patina tells the wok's story – its heat history, the dishes it has prepared, the care it has received. In an era of disposable cookware, this living surface represents the antithesis: cookware that improves with age and use.

Contemporary cooks often misunderstand the black coating's purpose. It's not merely cosmetic or purely functional – it's the visual manifestation of the wok's transformation from raw iron to seasoned cooking partner. That glossy black surface represents thousands of aligned molecules, a culinary fingerprint unique to each wok and its owner. Three applications of pork fat set this alchemy in motion, but the relationship continues evolving with every stir-fry, every steaming, every careful cleaning.

The resurgence of iron woks in professional kitchens worldwide has brought renewed appreciation for this ancient technique. As chefs rediscover the unparalleled heat control and flavor development possible with properly seasoned woks, the three-step pork fat method has transitioned from obscure tradition to essential skill. In mastering this process, modern cooks don't just preserve history – they create cookware capable of producing the most vibrant, technically perfect stir-fries imaginable.

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025